What becomes of old generals? At least one welcomes wounded Army Rangers for duck hunts at his place. What does that have to do with soldiering? By God’s grace, nothing at all.

BALD KNOB – Four Army Rangers walk into a backyard in Bald Knob.

Between the four of them, these soldiers have more than 20 deployments to the world’s hot spots. One soldier’s next trip is imminent, with the hope of being back in time for his wife to birth their first baby.

Why here? Duck hunting and Jim Daniel, the two being mostly inseparable.

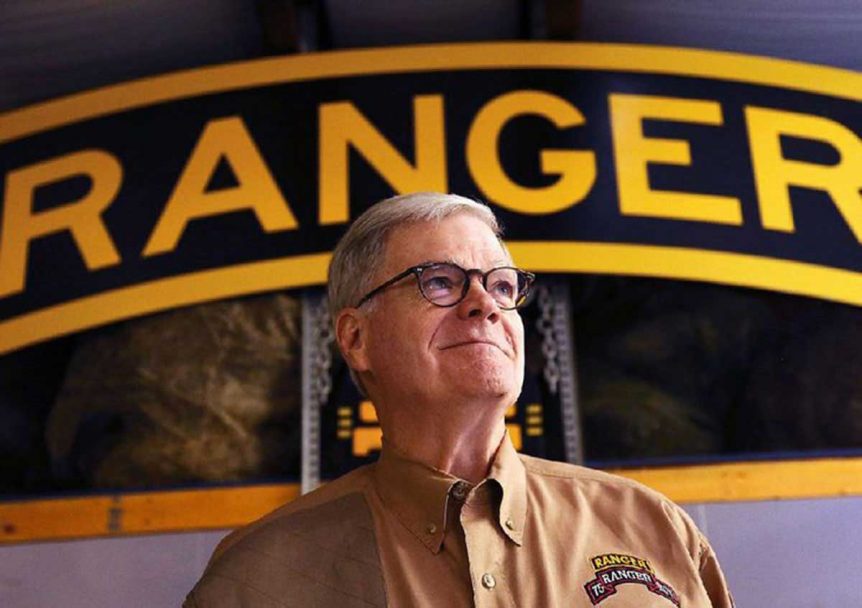

It’s the night before the opening of duck season, and this is the first wave of Rangers to drop in at what Daniel calls the duck house, an expansive home with a shop in the back that’s a cornucopia of duck hunting gear. Daniel is a retired Army brigadier general, who lives in Little Rock and here. His son, Shawn, is a soldier on active duty in Afghanistan.

Dennis Smith is hanging out in the backyard, too. He’s a retired Ranger, a command sergeant major, now living in Smiths Station, Ala. He was present at the inception of what is now known as Darby’s Warrior Support, a nonprofit whose mission is to provide Arkansas duck hunting experiences, and to provide scholarships and support to severely wounded and permanently disabled veterans who seek a college degree.

Date and place of birth: Dec. 17, 1939, Franklin County, N.C.

Best advice I ever got:If you can see it, you can be it. If you dream it, you can achieve it.

Fantasy Dinner Guests: Gordon Cosby, Thomas Merton and Pope Francis.

I’m currently reading:Merton’s No Man Is an Island.

Favorite vacation spot:Below Broad Street in Charleston, S.C.

Americans should be grateful: Your freedom is the most expensive thing you own, even if you didn’t pay for it yourself.

The army teachesselfless service and teamwork.

The clergy teachesthat, in service to others, you find your true self.

One word to sum me up: Relentless.

The reference is to William Orlando Darby, a Fort Smith native and organizer of the 1st Ranger Battalion in World War II.

This year, Smith said, up to 75 members of the Rangers and other special forces will have the chance to hunt ducks in Arkansas. That’s up from the 62 served last year and triple the 25 or so who hunted a few years back.

“There’s something different about waterfowl hunting,” Smith said, “just the experience of seeing the sky full of birds. It’s incredible. All of the experiences you had in the past go away for a moment. It’s a spiritual and emotional healing, the magic of the morning and the magic of the evening.”

Now, about those four Rangers. In a group, each with a beer, they look a lot like any other group of guys with beers, except fitter. Ethan Miller, a lieutenant colonel, is the regimental surgeon of the 75th Ranger Regiment. He has saved more lives, Dennis Smith said, than penicillin, to which Miller responded with a laugh. “He lies.”

Sgt. Ray Houston has been in the Army for five years, preceded by four years in the Navy. He’s got seven deployments between both services. Why the switch? “I wanted to play a more direct role in what’s happening over there.”

Is he a duck hunter?

“I’m about to be.”

Maj. Patrick Kelly, 16 years in the Army with five deployments, is even less of a duck hunter than Houston. “I’ve never hunted anything in my life.”

Sgt. 1st Class Nick Cunningham is a 10-year veteran from L.A. — Lower Alabama. The next week he was set to go on his fifth deployment. He’s the one with the pregnant wife. She naturally finds this next deployment problematic, “especially since I was going duck hunting. But I made a commitment to be here.”

Commitment. That sticks to Jim Daniel, who was in the Army from 1959 to 1990. He and Julia Ann have been married for 53 years. They have two children and four grandchildren.

Daniel is retired, with a resume he admits is way outdated, but on examination remains accomplished: bachelor’s degree from Clemson; master’s degrees in theology and education; a doctorate from a theological seminary; continuing education at Cambridge University in England and Harvard; ordained a Baptist clergyman in 1964.

In the Army, a rise from private to general; airborne, air assault, and the Ranger tab; command from platoon to assistant division commander for a mechanized infantry division.

“There aren’t many people who have had as many lives as I have,” he said. “It’s a strange pathway.”

Daniel’s meandering walk took him from infantry soldier to infantry officer to chaplain and back to infantry officer, in the process rising from private to brigadier general.

“I was an Army chaplain but left that role because my superior at the time said, ‘You should be commanding this unit.'”

Those transitions, Daniel said, “are part of the complexity of my life.”

Memorabilia packs his office. One thing that immediately draws the eye is a montage of three photos. In each is President Dwight D. Eisenhower and, of course, a tall, skinny soldier named Jim Daniel who was in officer candidate school at Fort Benning, Ga.

“I was told to say only ‘Yes, Mr. President; No, Mr. President,'” Daniel remembered. “He was as personable as any human I ever met.”

While Daniel was making conversation in the limited vocabulary ordered by his superiors, Ike was more voluble, at one point making reference to an infamous chapter in the career of Gen. George Patton, his slapping of a soldier Patton believed to be a malingerer.

Daniel recalled what Ike said: “You know, Georgie never meant to hurt that boy in North Africa.”

“Now why would a president say that to a 19-year-old wannabe officer?”

In faded red ink on one of the photos is an inscription: “To James Daniel, Best Wishes, Dwight Eisenhower.”

Also on the wall are photos of Daniel and his 1959 Clemson football team, which played in the Sugar Bowl, losing 7-0 to Louisiana State University. One of Daniel’s most prized possessions is a Sugar Bowl watch.

At Clemson, “I was a blocking dummy,” and a tailback, and the coach, Frank Howard, would tell him to “get your tail back on the bench.”

Star or rider of the pine, Daniel still appreciates the opportunity.

“Without that scholarship I would not be who I am today.”

Three things have shaped his life, Daniel said. First, his Christian faith, to which he came as a second lieutenant at Fort Benning. Second, his Army experiences. Third, his lifelong mentor, Gordon N. Cosby.

Cosby and Daniel connected in Washington, where Cosby pastored a church. He’d been a chaplain in World War II in the 101st Airborne Division. “He was the father I never had,” Daniel said.

Daniel recounted a tale from Cosby’s life in the hedgerows of France. “He crawled from foxhole to foxhole in the hedgerows. The soldiers would say, ‘Talk to me about God. Don’t give me any of that other stuff — I’m going to die tomorrow.’ And often they did.”

The radical obedience of the Rangers, plus his faith, Daniel said, instilled in him a sense of selfless service to others. “That’s the story of my life.”

“When Gordon died at 94,” Daniel said, “all of us adopted sons met in the Methodist church [Abraham] Lincoln attended” in Washington, and “there were 1,200 of us. His fatherly guidance and my faith are what I have organized my life around.”

Included in Daniel’s long life in the Army was duty at Camp Robinson in North Little Rock, 1982-1986, as commandant of the National Guard Professional Education Center.

Arkansas has something Daniel has chased all his life. Ducks. Lots and lots of ducks.

“I’m the only commander to be investigated for using a helicopter to scout ducks,” he said over a cup of coffee at the duck house. “I was not guilty of that.”

The coffee cups are worth a look. They are adorned with the Ranger crest and the words “Sua Sponte,” meaning “of their own accord.” Or as Daniel explained, “instant obedience. Don’t think about it. Instantly obey. If you’re told to jump off that cliff, jump.”

PHOTOGRAPHS

Many folks help out at the duck hunts around the state and the receptions for the soldiers. On this evening the volunteers included Rachel Smith of Nashville and Matthew Harbin of Searcy.

Smith, no relation to Dennis Smith, is a photographer who spends time around and with the soldiers, creating a photographic chronicle. This year is her fourth to do so.

“When they leave they get a complete DVD of their weekend experiences. I try to silently step around and take pictures so they can take them back and share.”

Smith met Jim Daniel when she lived in Searcy. A few years ago some bald eagles gathered at a reservoir nearby. So did photographers.

“We hit it off immediately,” Smith said. “We both have an appreciation for the beauty of God’s creation out here.”

There was some friendly competition, too.

“Of course I would say my pictures were better, and he would say his were. But Jim is far better. He’s an incredible photographer.”

“He’s one of the few people I know in life who’s the total package,” Smith said. “He wants everything to be perfect for these guys and he works harder than anyone to make sure that happens. He’s got a big, kind heart and a genuine love.”

Harbin is the local Chick-fil-A operator. His predecessor was involved with Daniel and the duck hunts, and now Harbin is on the board of Darby’s Warrior Support. His restaurant also donates food for the gatherings.

“I don’t think any of this would have happened without Jim’s drive to keep the focus on the soldiers,” Harbin said.

FATHER AND SON

Pictures of ducks in flight, photographed by Daniel, speckle the walls in the Bald Knob home. Ducks have been a constant in his life since he grew up hunting them in South Carolina.

“There’s something mystical about it,” he said. “Yes, it’s cold and painful, but it’s worth it.”

The sport connects with the Ranger ethos, Daniel said. The sport’s attractions include “a radical camaraderie beyond the ordinary.”

“When I pinned on that Ranger tab I expected more of myself,” Daniel said. “Duck hunting expects more of you than any other sport.”

Jim Daniel sees an intimacy in duck hunting to which combat soldiers can relate.

“Something happens in duck hunting. You sit in that duck blind and watch the sun come up. That’s intimate.”

He wanted his son, Shawn, to have that camaraderie.

“Where a son gets shaped is in the car, in the boat, in the duck blind with a colonel father talking about life and his experiences.”

Shawn Daniel absorbed those lessons. He’s a 1993 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he rose to first captain in his senior year. Shawn Daniel is a colonel, a Ranger currently in his eighth deployment to Afghanistan. By email, he recalled fishing with his father on Lake Maumelle when the latter got a lure hung up on a limb several feet under water.

“Before I knew what was happening, he was stripped down to his skivvies and diving into the chilly waters muttering something about ‘not leaving $4 at the bottom of the lake.’ Some would see his actions as frugal. I saw them as hard, determined and committed. I tried to emulate that, but I don’t know that I’ve ever mastered it quite to the level that he did.”

A SAFE PLACE

Hunters and helpers eventually gather in Daniel’s shop for food and a briefing on the next day’s activities. The shop is a duck hunter’s dream. Gun safes … shotguns … shells … waders … four-wheelers — name it, and it’s here, much of it donated.

“I show this,” Daniel said of the gear, “as a testimony to the generosity of Arkansans.”

There is one unusual artifact in the shop: Daniel’s one-star general’s flag, hanging in the back.

As a charity and a mission, these duck hunts for soldiers came out of hunts that included Shawn Daniel, Dennis Smith and others, an experience Jim and Julia Ann Daniel chose to extend to others.

“They offer each group a chance to relax in a welcoming and grateful environment,” Shawn Daniel said, “a chance to see a grateful nation hundreds of miles away from the nearest military installation in the heart of America.”

There’s an opportunity, he said, “to open up, if they choose to, about some of their experiences and scars — where no one would judge them.”

Many of the soldiers who come here to hunt are wounded, Jim Daniel said, either physically or mentally. Daniel and Julia Ann recalled the experience of one soldier. He came to the duck house wearing a sock cap. He was uneasy, and wandered around the house. At 3 o’clock one morning he told the Daniels about the explosion that wounded him.

“A big chunk of his skull was missing,” Jim Daniel said. “He had never told anyone about this. We gave him a place of safety and caring and intimacy, and that sock cap came off.”

“He came here frozen,” Julia Ann said, “and left warm and toasty.”